How does DNA move? How do cells communicate with each other? When it comes to these questions, it’s easy to think of molecular biologists behind the words. But as physics and mathematics senior Sullivan “Sully” Bailey-Darland knows, there are many more voices asking.

“My biggest worry for physics was that I would just be doing stuff about energy and electrons, and those are interesting, but they’ve been studied so much and involve a lot of the research I wasn’t as interested in,” he said. “My lab advisor has made me aware that physics is not a limiting degree. From what I can tell, it’s the most limitless degree.”

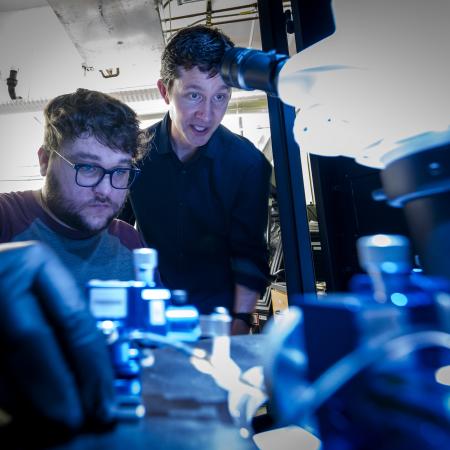

Bailey-Darland has found a full range of research opportunities from his time pursuing physics, mathematics and even chemistry at Oregon State. A future of discovery and experimentation has already begun for him as he forges ahead to graduate school at Cornell University.

Expanding the possibilities

During his first year, Bailey-Darland took part in the Undergraduate Research, Scholarship, & the Arts (URSA) Engage program. URSA Engage gives research opportunities to first- and second-years, as well as transfer students. As part of the program, students choose a faculty mentor to work with on their research projects. While searching through faculty mentor summaries for a project that interested him, Bailey-Darland saw a familiar name — Assistant Professor Kevin Brown.

Bailey-Darland had previously attended several seminars within the department of physics and recalled seeing Brown give a distinct presentation at one on linguistics, an uncommon topic for the field.

“He gave a seminar on modeling a language network and comparing it to different types of gases, and I thought that was really crazy,” Bailey-Darland said. Intrigued by Brown’s research, he decided to seek him out and landed a position doing computational programming in his laboratory group.

What he didn’t expect from the experience was a broader perspective of his major. Brown, who holds a doctorate in theoretical physics from Cornell University, studied biological systems for his Ph.D. His work as a physicist shattered the predetermined niche of the field Bailey-Darland had painted in his mind.

“Working at Oregon State made me want to do more interdisciplinary things…It made me aware that if you learn tools or skills from physics or math, you don’t have to necessarily be stuck only applying them to that field. And that’s exactly what biophysics is.”

“Dr. Brown made me aware of the possibilities for physics,” he said. “He introduced me to the idea that the field can be for any interesting problem, not just a physics problem.”

Biophysics, the field Brown based his doctorate on, appealed to Bailey-Darland through its interdisciplinary nature, a quality he values highly ever since beginning his research career.

“Working at Oregon State made me want to do more interdisciplinary things,” he said. “It made me aware that if you learn tools or skills from physics or math, you don’t have to necessarily be stuck only applying them to that field. And that’s exactly what biophysics is.”